In June of 2017 I wrote a blog for InfoWorld on How to handle the risks of hypervisor hacking. In it, I described the theoretical points where Virtual Machines (VMs) and hypervisors could be hacked. My crystal ball must have been well polished. Spectre and Meltdown prey on one of the points I described there.

What I did not predict is where the vulnerability would come from. As a software engineer, I always think about software vulnerabilities, but I tend to assume that the hardware is seldom at fault. I took one class in computer hardware design thirty years ago. Since then, my working approach is to look first for software flaws and only consider hardware when I am forced, kicking and screaming, to examine for hardware failure. This is usually a good plan for a software engineer. As a rule, when hardware fails, the device bricks (is completely dead), seldom does it continue to function. There is usually not much beyond rewriting drivers that a coder can do to fix a hardware issue. Even rewriting a driver is usually beyond me because it takes more hardware expertise than I have to write a correct driver.

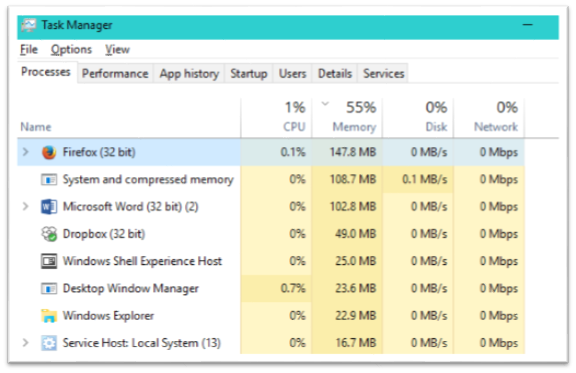

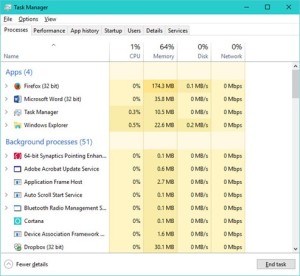

In my previous blog here, I wrote that Spectre and Meltdown probably will not affect individual users much. So far, that is still true, but the real impact of these vulnerabilities is being felt by service providers, businesses, and organizations that make extensive use of virtual systems. Although the performance degradation after temporary fixes have been applied is not as serious as previously estimated, some loads are seeing serious hits and even single digit degradation can be significant is scaled up systems. Already, we’ve seen some botched fixes, which never help anyone.

Hardware flaws are more serious than software flaws for several reasons. A software flaw is usually limited to a single piece of software, often an application. A vulnerability limited to a single application is relatively easy to defend against. Just disable or uninstall the application until it is fixed. Inconvenient, but less of a problem than an operating system vulnerability that may force you to shut down many applications and halt work until the operating system supplier offers a fix to the OS. A flaw in a basic software library can be worse: it may affect many applications and operating systems. The bright side is that software patches can be written and applied quickly and even automatically installed without computer user intervention— sometimes too quickly when the fix is rushed and inadequately tested before deployment— but the interval from discovery of a vulnerability to patch deployment is usually weeks or months, not years.

Hardware chip level flaws cut a wider and longer swathe. A hardware flaw typically affects every application, operating system, and embedded system running on the hardware. In some cases, new microcode can correct hardware flaws, but in the most serious cases, new chips must be installed, and sometimes new sets of chips and new circuit boards are required. If installing microcode will not fix the problem, at the very least, someone has to physically open a case and replace a component. Not a trivial task with more than one or two boxes to fix and a major project in a data center with hundreds or thousands of devices. Often, a fix requires replacing an entire unit, either because that is the only way to fix the problem, or because replacing the entire unit is easier and ultimately cheaper.

Both Intel and AMD have announced hardware fixes to the Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities. The replacement chips will probably roll out within the year. The fix may only entail a single chip replacement, but it is a solid prediction that many computers will be replaced. The Spectre and Meltdown vulnerabilities exist in processors deployed ten years ago. Many of the computers using these processors are obsolete, considering that a processor over eighteen months old is often no longer supported by the manufacturer. These machines are probably cheaper to replace than upgrade, even if an upgrade is available. More recent upgradable machines will frequently be replaced anyway because upgrading a machine near the end of its lifecycle is a poor investment. Some sites will put off costly replacements. In other words, the computing industry will struggle with the issues raised by Spectre and Meltdown for years to come.

There is yet another reason vulnerabilities in hardware are worse than software vulnerabilities. The software industry is still coping with the aftermath of a period when computer security was given inadequate attention. At the turn of the 21st century, most developers had no idea that losses due to insecure computing would soon be measured in billions of dollars per year. The industry has changed— software engineers no longer dismiss security as an optional afterthought, but a decade after the problems became unmistakable, we are still learning to build secure software. I discuss this at length in my book, Personal Cybersecurity.

Spectre and Meltdown suggest that the hardware side may not have taken security as seriously as the software side. Now that criminal and state-sponsored hackers are aware that hardware has vulnerabilities, they will begin to look hard to find new flaws in hardware for subverting systems. A whole new world of hacking possibilities awaits.

We know from the software experience that it takes time for engineers to develop and internalize methodologies for creating secure systems. We can hope that hardware engineers will take advantage of software security lessons, but secure processor design methodologies are unlikely to appear overnight, and a backlog of insecure hardware surprises may be waiting for us.

The next year or two promises to be interesting.