For the last two decades, we’ve been in an era of free services: internet searches, social media, email, storage. Free, free, free. My parsimonious head spins thinking of all that free stuff.

Social and technical tectonic plates are moving. New continents are forming, old continents are breaking up. Driven by the pandemic and our tumultuous politics, we all sense that our world is changing. 2025 will not return to 2015. Free services will change. In this post, I explain that one reason free digital services have been possible is they are cheap to provide.

I’m tempted to bring up Robert Heinlein, the science fiction author, and his motto, TANSTAAFL (There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch), as a principle behind dwindling free services, but his motto does not exactly apply.

Heinlein’s point was that free sandwiches at a saloon are not free lunches because customers pay for the sandwiches in the price of the drinks. This is not exactly the case with digital free lunches. Digital services can be free because they cost so little, they appear to be free. Yes, you pay for them, but you pay so little they may as well be free.

A sandwich sitting beside a glass of beer costs the tavern as much as a sandwich in a diner, but a service delivered digitally costs far less than a physical service. Digital services are free like dirt, which also appears to be free, but it looks free because it is abundant and easily obtained, not because we are surreptitiously charged for it.

Free open source software and digital services

One factor behind free digital services is the free software movement which began in the mid -1980s with the formation of the Free Software Foundation. The “free” in Free Software Foundation refers more to software that can be freely modified rather than to products freely given away, but most software under the Free Software Foundation and related organizations is available without charge. Much open source software is written by paid programmers, and is therefore paid for by someone, but not in ways that TANSTAAFL might predict.

The workhorse utilities of the internet are open source. Most internet traffic is Hyper Text Transmission Protocol (HTTP) packets transmitted and received by HTTP server software. The majority of this traffic is driven by open source Apache HTTP servers running on open source Linux operating systems. Anyone can get a free copy of Linux or Apache. Quite often, servers in data centers run only open source software. (Support for the software is not free, but that’s another story.)

So who pays for developing and updating these utilities? Some of the code is volunteer written, but a large share is developed on company time by programmers and administrators working for corporations like IBM, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Cisco, coordinated by foundations supported by these same corporations. The list of contributors is long. Most large, and many small, computer companies contribute to open source software utilities.

Why? Because they have determined that their best interest is to develop these utilities through foundations like the Linux Foundation, The Apache Foundation, Eclipse Foundation, Free Software Foundation, and others, instead of building their own competing utilities.

By collaborating, they avoid wasting money when each company researches and writes similar code or places themselves in a vulnerable business position by using utilities built by present or potential competitors. It’s a little like the interstate highway system. Trucking companies don’t build their own highways, and, with the exception of Microsoft, computer companies don’t build their own operating systems.

Digital services are cheap

Digital services are cheap, cheaper than most people imagine. Free utilities contribute to the cheapness, but more because they contribute to the efficiency of service delivery. The companies that use the open source utilities the most pay for them in contributed code and expertise that amounts to millions of dollars per year, but they make it all back because the investment gives them an efficient standardized infrastructure which they use to build and deliver services that compete on user visible features that yield market advantages. They don’t have to compete on utilities that their customers only care about when they fail.

Value and cost of digital services are disconnected

We usually think that the cost of a service is in some way related to the value of the service. Digital services break that relationship.

Often, digital services deliver enormous value at minuscule cost, much lower cost than comparable physical services. Consider physical Encyclopedia Britannica versus digital Wikipedia, two products which offer similar value and functionality. A paper copy of Britannica could be obtained for about $1400 in 1998 ($2260 in 2021 dollars). Today, Wikipedia is a pay-what-you-want service, suggested contribution around $5 a month, but only a small percentage of Wikipedia users actually donate into project.

Therefore, the average cost for using Wikipedia is microscopic compared to a paper Britannica. You can argue that Encyclopedia Britannica has higher quality information than Wikipedia (although that point is disputable) but you have to admit that the Wikipedia service delivers a convenient and comparable service whose value is not at all proportional to its price.

Digital reproduction and distribution is cheap

The cost of digital services behaves differently than the cost of physical goods and services we are accustomed to. Compare a digital national news service to a physical national newspaper.

The up-front costs of acquiring, composing, and editing news reports are the same for both, but after a news item is ready for consumption, the cost differs enormously. A physical newspaper must be printed. Ink and paper must be bought. The printed items must be loaded on trucks, then transferred to local delivery, and hand carried to readers’ doorsteps. Often printed material has to be stored in warehouses waiting for delivery. The actual cost of physical manufacture and delivery varies widely based on scale, the delivery area, and operational efficiency, but there is a clear and substantial cost for each item delivered to a reader.

A digital news item is available on readers’ computing devices within milliseconds of the editor’s keystroke of approval. Even if the item is scheduled for later delivery, the process is entirely automatic from then on. No manpower costs, no materials cost, minuscule network delivery costs.

The reproduction and network delivery part of the cost of an instance of service is often too small to be worth the trouble to calculate.

My experience with network delivery of software is that the cost of reproducing and delivering a single instance of a product is so low, the finance people don’t want to bother to calculate it. They prefer to lump it into corporate overhead, which is spread across products and is the same whether one item or a million items are delivered. The cost is also the same whether the item is delivered across the hall or across the globe. Physical items are often sit in expensive rented warehouses after they are reproduced. Digital products are reproduced on demand and never stored in bulk.

Stepwise network costs

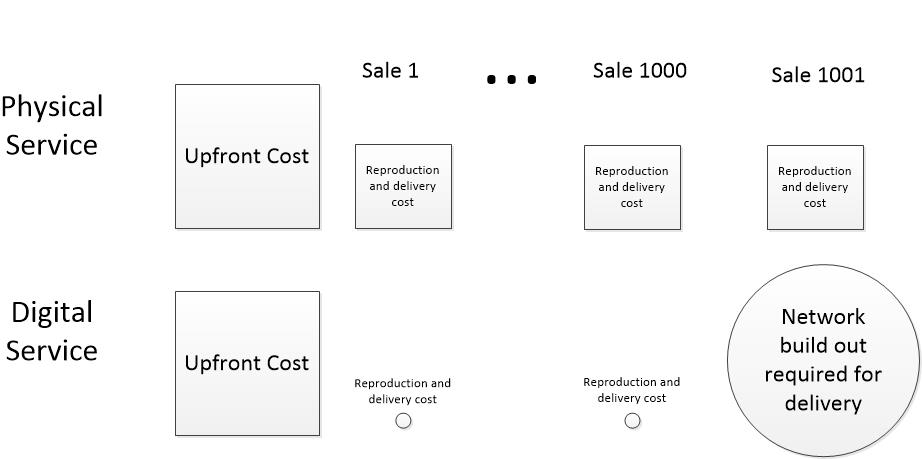

Network costs are usually stepwise, not linear, and not easily allocated to the number of customers served. Stepwise costs means that when the network infrastructure is built to deliver news items to 1000 simultaneous users, the cost stays the about same for one or 1000 users because much of the cost is a capital investment. Unused capacity costs about the same as used capacity— the capacity for the 1000th user must be paid for even though 1000th user will not sign on for months.

The 1001st user will cost a great deal, but after paying out to scale the system up to, say, 10,000 users, costs won’t rise much until the 10,001st user signs on, at which point another network investment is required. Typically, the cost increment for each step gets proportionally less as efficiencies of scale kick in.

After a level of infrastructure is implemented and paid for, increasing readership of digital news service does not increase costs until the next step is encountered. Consequently, the service can add readers for free without affecting adversely affecting profits or cash flow, although each free reader brings them closer to a doomsday when they have to invest to expand capacity.

Compare this to a physical newspaper. As volume increases, the cost per reader goes down as efficiency increases, but unlike a digital service, each and every new reader increases the overall cost of the service as the cost of manufacturing and distribution increases with each added reader. The rate of overall increase may go done as scale increases, but the increment is always there.

Combine the fundamental low cost of digital reproduction and distribution with the stepwise nature of digital infrastructure costs and digital service operators can offer free services much easily and more profitably than physical service providers.

The future

I predict enormous changes in free services in approaching months and years, but I don’t expect a TANSTAAFL day of reckoning because providing digital services is fundamentally much cheaper than physical services.

I have intentionally not discussed the ways in which service providers get revenues from their services, although I suspect most readers have thought about revenue as they read. The point here is that digital services are surprisingly cheap and their economic dynamics are not at all like that of physical goods and services.

As digital continents collide, I expect significant changes in free digital services, changes that will come mainly from the revenue side and our evolving attitudes toward privacy and fairness in commerce. These are a subjects for future posts.