Like an echocardiogram that shows the blood flowing through a beating heart, the task shows the flow of activity on a computer. On Apple products, the task list is called the activity list. In Unix and its derivatives, such as Linux and Android, the task list is usually called the process list. In all of these operating systems, a task, activity, or process, whichever you want to call it, is an executing program. Most of the time, there are a lot of them.

Processors

A processor can only run one process at a time, but they switch between processes so rapidly it looks like a processor is running many processes at the same time. All the processes on the task list have been started but have not finished. Some are waiting for input, others are waiting for a chance to use some busy resource like a hard drive, but all are entitled to some time on the processor when their turn comes up.

Many computers today have more than one processor, which increases the number of processes that can run at one time and the amount of time a computer can give to each process. Different operating systems have different strategies for switching between processes, but all the strategies are like plate spinning acts. The plate spinner hurries from plate to plate, giving plates a spin when they begin to slow down and need attention. (If you don’t know what plate spinning is, see it here.) The processor does the same thing, executing a few instructions for a program, then rushing to the next process.

Processes

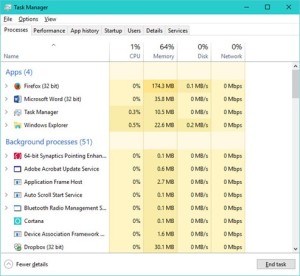

All the processes, both active and waiting, show up on the task list. That includes malware as well as legitimate processes. If you can spot a bad guy on the process list, you can kill it. The kill may not be permanent, processes can regenerate themselves, but it is usually worth a try. The challenge is to sort the good from the bad. Unless you know what you are shooting at, you might crash the entire computer or lose data, so be careful. You could find yourself restoring your entire system from a backup. Nevertheless, this is one area where you can strap on your weapons and wage open warfare against malware.

When I see an unfamiliar process on the task list, I usually run to Google. Most of the time, Google results tell me that the process is something innocuous that I hadn’t noticed before, but not always. By the way, be a little careful when Googling. There are questionable companies out there with sites that will appear in the search result and try to take advantage of you by offering unnecessary clean up services or dubious downloads. Microsoft will give you trustworthy advice, as will the established antivirus companies, but avoid sending money or installing programs from places you have never heard of. Some may be legitimate, but not all. Above all, don’t let anyone log into your computer remotely without rock solid credentials.

CPU Time

The task list tells you more than just the names of the running processes. There are number of readouts on the state of each process and the resources it is using. The one I usually look at first is the percentage of CPU time being taken and the accumulated CPU time. (Click at the top of the column to sort the processes by the metric.) Both of these metrics show the amount of time a process consumes on the processor–the amount of time the plate spinner has spent spinning the plate. A program that consumes more CPU time is using an extra share of the system’s most critical resource. Shutting down a high CPU consumer will do more to improve your computer’s performance than halting a low CPU consumer.

Some high-consumer processes are legitimate. For example, you will often see a browser using a lot of CPU time. That is because a browser does a lot of work. Any computing that takes place in web page interactions is chalked up to the browser. Some internal system processes, such “system interrupts,” do a lot of work also and rank high on CPU consumption. If you see an installed application that is hogging down CPU, you might check its configuration. There may be adjustments that will reduce consumption. Google will help you find what to do, but keep track of your changes so you can change them back if they don’t work. If you don’t use the program much, perhaps turning it off would be a good idea. When a high consumer happens to be malware, put a high priority on scrubbing it out. A high CPU-consuming malware is like a blockage in a coronary artery. You’ll feel much better without it.

Next Time

There’s more to the task list. Next time.