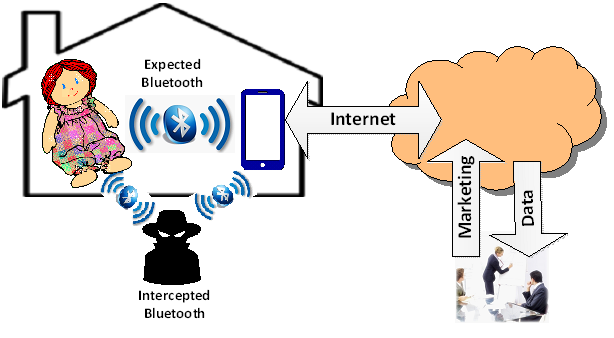

The Cayla doll story is frightening. The unintended consequences of a clever child’s toy amount to an invasion of child privacy. I expect more such stories. Devices now in homes don’t just offer entertainment and convenience. They can also open doors to corporate and criminal intrusion. TV’s, refrigerators, along with our phones and laptops can all have cameras and microphones. Without your permission, someone could control these from outside your home.

Threat assessment

Security professionals follow a procedure called “threat assessment” to spot potential dangers. Threat assessment is a series of questions. Their answers yield a clear picture of threats. The questions are common sense, but you may not always think to ask them.

I recommend that before you install any device in your home or business, especially those connected to the internet, you go through a threat assessment. You may already do so without realizing it. Think through each of the five questions below. These questions apply to almost all computer security. The next five apply to non-computer devices connected to the network.

The basic checklist

- What am I protecting? Most often, it is privacy of your family or business. Cayla can listen to you and your child and transmit what it hears to an unknown intruder or a cloud data business. The business or an intruder can speak to your child without your knowledge. Your television may record and analyze the conversations in your living room. Other devices may have similar abilities. Most often, you are protecting yourself from outside interference in your life.

- Where does the threat come from? The source could be a business putting together a portfolio on you that they will use to sell things to you. Less likely, but still possible, the source may be a sinister criminal planning some kind of assault. A government agency, for good or bad, could use the device to collect information on you.

- How likely is the threat? You probably know that data organizations collect data on you. And you have noticed that they have guessed whether you prefer heavy equipment parts or needlework supplies. On the other hand, the FBI probably hasn’t picked your refrigerator to monitor.

- How great is the danger? Ads targeted to your online search profile may annoy you, but the danger to your person is slight. But a criminal stalker monitoring your phone conversations through your Bluetooth headset may be dangerous.

- What are you willing to sacrifice for protection? Threats can be stopped, but is the effort is worth the benefit? All direct cyberthreats can be stopped or severely curtailed by going cash only and abstaining from the use of all electronic devices. Does the threat justify the sacrifice?

The Internet of Things

The threats here are from the Internet of Things (IoT), devices connected to the network but not usually called computers. The IoT is uniquely dangerous in two ways. First, IoT devices sneak in on us. We see them, but don’t think of them as computers connected to the internet. Even though many people have an idea of the threats involved in network computing, the IoT slips beneath their radar. Second, the designers of IoT devices often have no concept of good security practices and the devices are often shockingly vulnerable.

Questions for IoT security

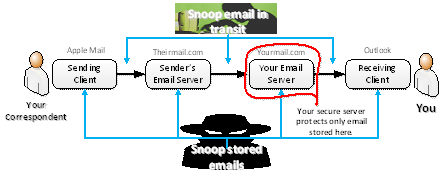

- Find out how it connects to the network. Hard wiring, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and cellular are the main ways.

- Can you unplug it from the network? How easily? The first step when you suspect some kind of intrusion is to disconnect from the network. Make sure you can. Many IoT devices can’t be switched off like a laptop or desktop. If hackers remotely unlock your front door, you must stop them immediately. Don’t put yourself in a position where you must call a locksmith to install a new lock to keep your door closed.

- Are logs kept of who tinkers with the device? When the tinkering happened? The location of the tinkerer?

- Does the device collect data? If so, what is it and who has access to it? Can you control what is collected and who has access?

- Can the device firmware be updated with security fixes? Can it be done automatically?

These questions may not be easy to find answers for. Marketing literature is often sketchy or even deceptive on security. Engineering documents are better, but hard or impossible to get. However, even partial answers help evaluate the threat and underpin informed choices.