Almost everyone knows that they should secure their home wi-fi network, but many people don’t realize that in addition to your wi-fi password, you should also set the password for your home network router. I promised at my presentation at the Ferndale Public Library on personal computer security that I would explain why and how to change your router password. This blog fulfills that promise.

On Saturday March 7 and 14, 3:00 pm , I will repeat the Ferndale presentations I gave on personal computer security and privacy online at the Lynden Public Library.

Your Wi-Fi Network Password

Today, establishing a password for your network is almost automatic. When you set up your home network with your network service provider, like Comcast, you are prompted to use a password, often printed on a label stuck to the modem-router combination supplied by your network service provider.

I suggest you change the supplied password to one of your own choice for two reasons: first if your provider has a dishonest employee (let’s face it – that does happen on rare occasions) they won’t have access to your network password. Consequently, if your provider has to work on your system, they’ll have to ask for the password. That may be a slight inconvenience, but I prefer it that way. The risk to using a unique network password supplied by your network service provider is not great, but setting your own password is easy, so I prefer to avoid the small risk.

Second, the provider-supplied password is random and hard to remember. Your home network press word is one you have to use infrequently but you do have to use it when you add a new device. I prefer a password I can remember instead of having to find the sticker, write the password down on paper, use it, then remember to destroy the paper so a neighbor kid won’t pick it up and run up my wi-fi bill streaming bandwidth-hog video games. A long nonsense phrase can be both hard to crack and easy to remember. Choose a phrase that doesn’t get hits on Google searches, like “3horsesdrank2muchcarrotjuice!”.

I would not try to store your wi-fi network password in a password manager. You might be able to do it, but it will probably be too awkward to bother with. Most password managers are not designed to interact with wi-fi sign-ons. Choose your phrase and write it down, then store the paper in a safe place. Unless you are gaga for network gizmos, you’ll only use your network password a few times a year, so you might forget it. If you have a home safe for your important papers, that might be a good storage choice. You should be aware that stolen wi-fi is a master hacker’s network access of choice. They’ve been known to use directional antennas to pick up insecure or loosely secured wi-fi from blocks away.

As a side note, your router may have a button you can push to avoid having to look up and type in the network password when you add a new device. This method is not totally secure if you have an attentive hacker in your vicinity. I choose not to use the button.

If you think you are being victimized by bandwidth thieves, change your network password and set up a device white list on your router. I’ll explain what I mean by a white list in another blog.

Having set your network password, there is another password that you should take care of: your router password. Router passwords are not part of your first line of defense. A hacker must first break into your network in order to make use of your router password, but if you leave the default password on your router , which it will be if you don’t change it, a hacker who breaches your network can do much more damage than one who can’t get to your router.

Routers

Your router is your connection to the Internet. It is a specialized computer that routes messages to and from the computers on your home wi-fi network to the rest of the network. As computers go, a home router is very good at what it does, but it could be replaced by an ordinary personal computer running special programs. Early home networks were often implemented by designating a PC as the local network router and loading it with routing software and extra network interface cards, but home routers are now so cheap and convenient, I don’t think anyone does that anymore. Today, most home routers are a combination device comprised of a modem, which transforms incoming signals on the wire connection to something usable by the home network, a wireless radio transmitter-receiver, and a router.

Typically, you access your home router today by logging on through a web browser. After you log on, you can change the way your home network interacts with the network and your network provider. The default settings on your router fairly effectively protect you from intrusion from the outside. Fresh out of the box, home routers are set up so that all interaction with computers outside the home network must originate from inside the home network. Although it may seem like the outside world is always sending you stuff, almost without exception, a computer on your home network has initiated an interaction and the outside world is responding to its requests. This fundamental pattern can be changed in many ways by changing the configuration of the router, sometimes for good reason. For example, some group interactive games require a different communications pattern. But criminals would like nothing better than to be able to send messages to your home devices at will. A bad guy with your router password could fix it so you can’t get to your own network or arrange to use your network to attack others. Changing your router’s password to something only you know ensures that only you can mess with it.

Changing a Router Password

Changing a router password is not difficult, but it could take you into unfamiliar territory. You may want to call in an expert to help you out. Never change anything but the router password if you do not fully understand what you are changing.

Overview

Here are the steps:

- Find your router default administrator name from the documentation that came with the router. Usually, the name is “admin” and the password is “password”, but not always.

- Determine the router IP address.

- Bring up the router in your web browser and enter the admin name and password.

- Navigate to the place where you can change the password.

- Change the password.

- Store it in your password manager. (Password managers handle router passwords just fine because you access them through your web browser.)

How To Determine Router IP Address

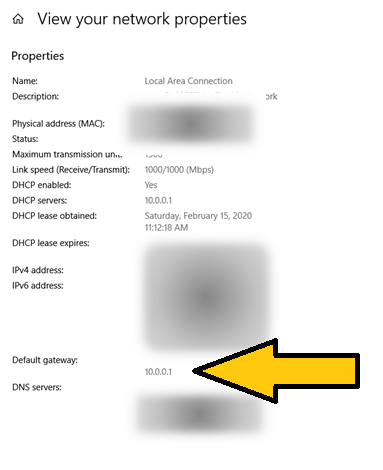

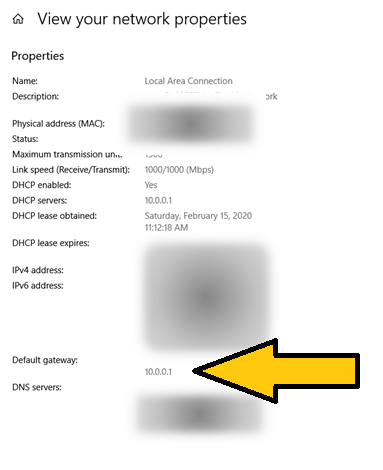

You can determine the router address from any device on your home network because the most basic requirement for connecting to the Internet is knowing the address of the router that controls the Internet connection. Some devices are easier than others. On a Windows 10 desktop, laptop, or tablet, bring up Settings (the gear symbol). Select Network & Internet, which will open the “Status” page. Towards the bottom of the page select “View your network properties.” You will see a page something like this:

Windows refers to the router IP address as the “Default Gateway.” On Apple, you can do something similar going to “System Preferences” and clicking on the “Network” icon and look for the “Router” label.

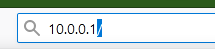

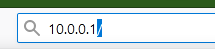

Router IP addresses are often “10.0.0.1” or “198.168.0.1”. If you want to skip finding the correct address, odds are good that you will get your router by trying these. If both fail, try “10.0.1.1” or “198.168.1.1”. Beyond those guesses, I’d take the long way and look up network properties.

Access Router with Web Browser

All you have to do is type your router IP address into the address line in your web browser, like this:

What will appear on the screen will depend on the router. You will probably be challenged for a username and password. If you haven’t changed them, they will be the factory-set default for the router. You can look them up in the documentation for your router. Most likely, they are “admin” and “password” or something equally obvious. You are likely to find documentation for your router, or router-modem combination online. Look for the make and model on the physical device and search online.

Change Router Password

At this point, you are on your own with your router documentation, although the steps to change the password will probably be obvious. If you use a password manager, it will probably offer to generate a random password and store it for you. I would consider taking the offer.

While you are logged on to your router, take a look around, although I would be cautious about changing anything unless you know what you are doing. Your router is the control center for your home network and the key to home network security. An intruder with access can open your network up to all sorts of mischief. That is why changing from the default password, which is accessible to anyone, is so important.