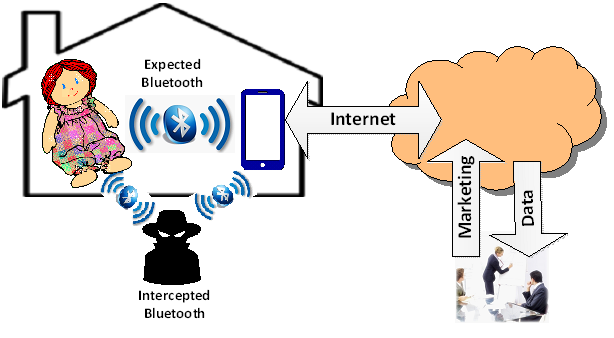

Over a year ago I published Seven Rules for Bluetooth at Starbucks. Recently, Armis, a security firm specializing in the Internet of Things (IoT), announced a new set of Bluetooth vulnerabilities they call BlueBorne. If you read “Seven Rules”, you have a good idea of what BlueBorne is like: hackers can get to your devices through Bluetooth. They can get to you without your knowledge. Windows, Android, Apple, and Linux Bluetooth installations are all vulnerable. Most of the flaws have been patched, but new ones are almost certain to be discovered.

Some of the flaws documented in BlueBorne are nasty: your device can be taken over silently from other compromised devices. Using BlueBorne vulnerabilities, hackers do not have to connect directly to your system. Someone walks within Bluetooth range with a hacked smartphone and you are silently infected. Ugly. Corporate IT should be shaking in their boots, and ordinary users have good reason to be afraid.

What should I do?

A few simple things make you much safer.

- Be aware of your surroundings. Bluetooth normally has a range of 30 feet. More with special equipment, but whenever you don’t know who might be snooping within a 30-foot radius sphere, you are vulnerable. That’s half way to a major league pitcher’s mound and roughly three floors above and below.

- Keep your systems patched. The problems Armis has documented in BlueBorne have been patched. Don’t give the bad guys a free ticket by leaving known soft spots unprotected. Make them discover their own holes. By patching regularly and quickly, you cut out the stupid and uninformed hackers. Smart hackers are rare.

- Turn Bluetooth off when you are not using it or you enter a danger zone. When Bluetooth is turned off, you are safe from Bluetooth attacks, although you may still be affected by malware placed on your device while Bluetooth was turned on.

The seven rules for Bluetooth I published a year ago are still valid. Follow them.

Seven basic rules for Bluetooth

- Avoid high-stakes private activities, like banking transactions, when using Bluetooth in public.

- If you are not using Bluetooth, turn it off!

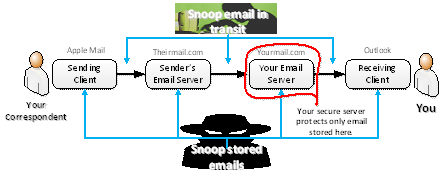

- Assume your Bluetooth connection is insecure unless you are positive it is encrypted and secured.

- Be aware of your surroundings, especially when pairing. Assume that low security Bluetooth transmissions can be snooped and intercepted from 30 feet in any direction, further with directional antennas. Beware of public areas and multi-dwelling buildings.

- Delete pairings you are not using. They are attack opportunities.

- Turn discoverability off when you are not intentionally pairing.

- If Internet traffic passes through a Bluetooth connection, your firewall may not monitor it. Check your firewall settings.