Do not act on this post without discussing it with your physician or healthcare professional. I have some thoughts you and your physician may want to consider, but this is not the place for health advice. Make health decisions by consulting with physicians and health professionals, not software engineers

Let me say the worst out front, hackers exploiting weaknesses in Bluetooth-enabled electronic medical devices could kill their victims. However, given the currently known vulnerabilities, the feat would be physically difficult, require a high level of skill, and be unreliable as an assassination method. More likely, these devices could be the basis for threats and extortion similar to ransomware.

That being said, I don’t think anyone should feel immediately threatened by Bluetooth medical devices. Some recognized Bluetooth vulnerabilities have troubling potential, but only potential. Researchers have found vulnerabilities that are theoretically exploitable, but no exploits have been seen. In the meantime, engineers are scrambling to patch the weak spots and the engineers have a good chance to beat the criminals.

Bluetooth Technology

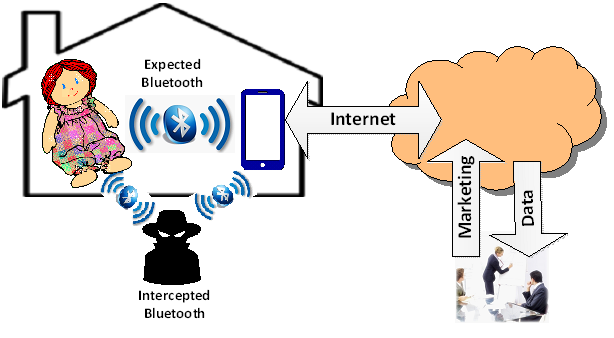

Bluetooth is a technology for connecting computer peripherals wirelessly. It is intentionally designed to work only at short distances; thirty feet is the designated limit for reliable operation, although the functional range can be broader. Unlike Wi-Fi or cellular signals, Bluetooth is not good at penetrating walls and other barriers.

I use Bluetooth headphones, mice, styluses, and keyboards all the time. Good riddance to pesky cables and cords. But Bluetooth is not always secure. For example, the National Security Agency bans Bluetooth cellphone headphones for discussing classified information. The Cayla doll of a few Christmases ago had some disturbing security flaws— not all due to Bluetooth, but Bluetooth was a factor. See Checklist to Avoid the Next Cayla Doll for some advice on using Bluetooth in general. I wrote some rules for using Bluetooth safely a few years ago that are still good. Seven Rules for Bluetooth at Starbucks.

Like many computing standards, Bluetooth is designed to work in many different situations by using some features in one implementation but not in others. For example, one of the most vulnerable— and annoying— aspects of Bluetooth usage is pairing, the process of connecting two Bluetooth devices. The standard document lists several different ways that pairing can work. The most popular, called “Just works,” freely connects any device to any other: easy but totally insecure. Most people don’t really care if an intruder overhears music from their phone and prefer the ease of “Just works” pairing, but the NSA takes issue with eavesdropping on classified info, hence the banned headphones.

Other pairing methods require exchange of passwords and other codes. They are a hassle, but more secure and therefore sometimes necessary. For example, Bluetooth keyboards often use more secure pairing because most people would rather that the stranger at the next table at Starbucks not be able to type commands into their laptop. The manufacturers of these devices have to balance convenience and ease of use with security. I have to say, for a product manager whose salary depends on producing easily sold products, choosing ease-of-use is tempting. Security is often said to drive away customers.

Bluetooth Medical Device Vulnerabilities

Bluetooth is great for users of medical devices like implanted pacemakers and defibrillators, insulin pumps, continuous blood sugar monitors, and other life-saving gadgets. Leads that connect internal devices to external controls are open wounds that invite infection and require constant effort to keep sanitary. Connecting an external device to a controller with physical cables is a nuisance. Mouse cables are annoying, cables that snake through clothing are worse. Bluetooth wireless connections eliminate many of these issues.

A security group in Singapore has published what are called the SweynTooth vulnerabilities, a list of known flaws in Bluetooth implementations that could compromise a number of Internet of Things, Smart-home, wearable, and other gadgets including medical devices. Details here. I’ve examined these vulnerabilities and divide them into three groups:

- Device crashes

- Denial of Service issues— overwhelming the device by bombarding it with unwanted messages

- Device takeovers

The first two groups of vulnerabilities lead to a crash or throwing the device into an overwhelmed state in which it effectively stops working. The device has to be restarted, but it will most likely return to normal operation after reboot. These issues are annoyances, perhaps extreme annoyances, but I find it hard to imagine they are life threatening. Most of the SweynTooth vulnerabilities fall into this class.

One SweynTooth vulnerability has an extremely disturbing outcome: device takeover. In this scenario, a criminal takes control of the medical device. If the device is a defibrillator, the criminal could repeatedly defibrillate a normally functioning heart. Death is a reasonable expectation. A compromised pacemaker could slow the victim’s heart rate to the point of brain death and organ failure, or accelerate the rate and cause an arrhythmia. A compromised insulin pump could overdose a victim with insulin. In each case, death is possible.

Outcomes

In the face of these dangers, how likely are these outcomes? In my judgement, possible but improbable.

First, Bluetooth has limited range. The attacker must be close to the victim. In most cases, in sight of the victim. Bluetooth can penetrate walls and other barriers, but not well. This is excellent news for potential victims because criminals have to identify their targets and get close to attack. This is not good, but much better than situations where the attacker can anonymously scan the network for potential victims and attack from the other side of the planet. An operational non-medical suggestion: if you use a vulnerable device, avoid broadcasting the fact to those around you.

Second, these vulnerabilities are not simple to exploit. An attacker has to be familiar with both Bluetooth technology and the implementation of the medical device in order to launch an attack. This eliminates casual criminals and script kiddies, but leaves the door open for military or government operations.

The upshot is that only significant targets are likely to become victims. Who is a target? Well, if you have upset North Korea and have a vulnerable embedded defibrillator, conceivably, North Korean cybercommand could send a highly trained operative to get within Bluetooth range of you and flub your defibrillator. Most people don’t fall in that class.

More likely, a criminal group might hack into a medical device supplier’s records and get a list of users of vulnerable devices, get within Bluetooth range and harass a few users, then demand ransom from the supplier. Might work, but regular ransomware is orders of magnitude less work and risk for the criminals.

Final Words

Given these circumstances, what would I do? Discuss it with my doctors. Persuade them to demand that device suppliers address the SweynTooth vulnerabilities. I would tell my doctor that I would rather avoid using a vulnerable device, but I would use one if the medical advantages justify the risk. Nevertheless, those attorneys who advertise on television will reap the benefits if victims start keeling over.